《英语学术论文写作》沈玉如主编|(epub+azw3+mobi+pdf)电子书下载

图书名称:《英语学术论文写作》

- 【作 者】沈玉如主编

- 【页 数】 204

- 【出版社】 成都:西南交通大学出版社 , 2020.01

- 【ISBN号】978-7-5643-7355-9

- 【分 类】英语-论文-写作-高等学校-教材

- 【参考文献】 沈玉如主编. 英语学术论文写作. 成都:西南交通大学出版社, 2020.01.

图书封面:

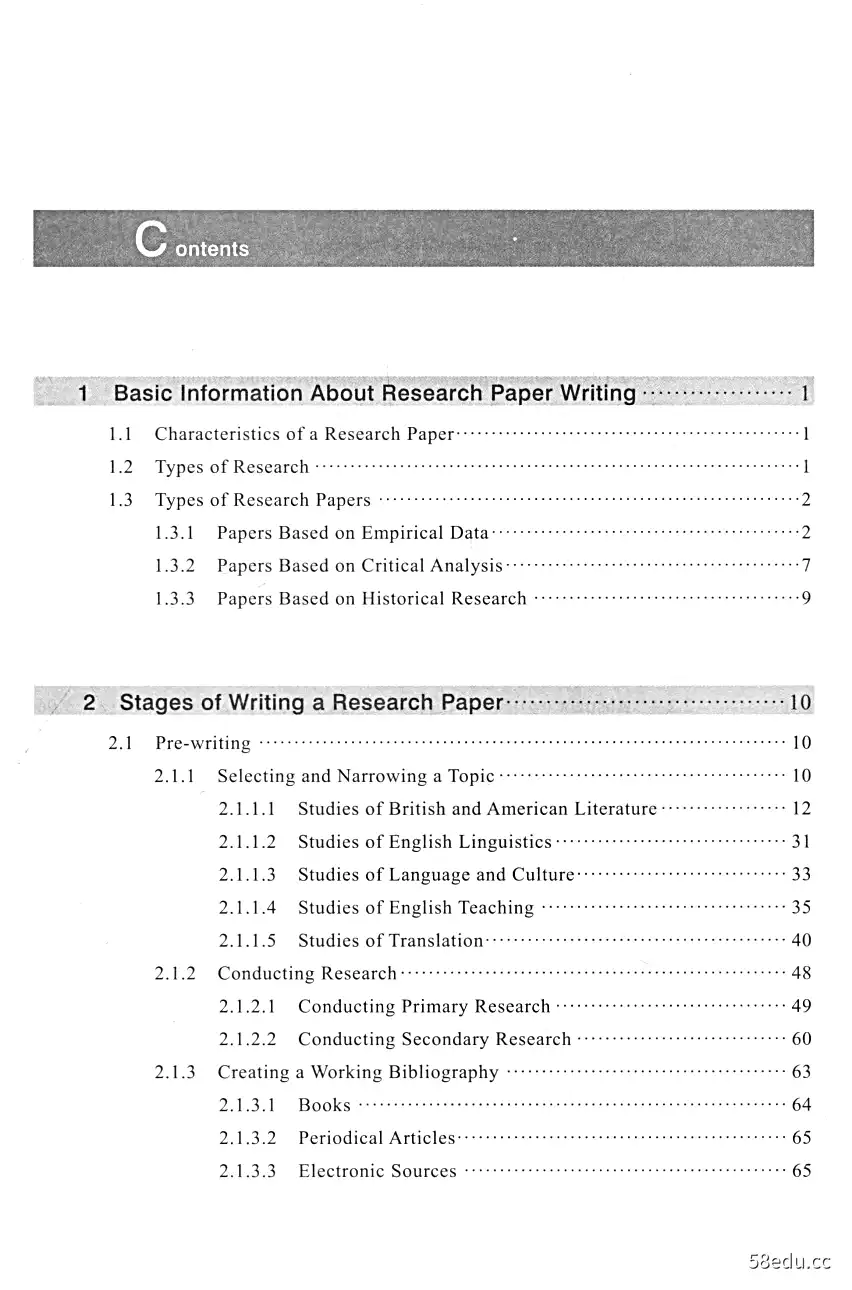

图书目录:

《英语学术论文写作》内容提要:

作者结合多年英语写作教学和学术论文写作教学经验以及指导学生论文过程中发现的问题,基于“知行结合”的原则,编写了本教材。第一章简要介绍学术(研究)论文的基本特征、研究类型及学术论文类型;第二章介绍学术论文写作过程和主要要素,提供大量实例帮助学习者内化所学知识;第三章介绍三种国际通用的论文格式在文献引用和标注及文献著录方面的规范,提供大量实例供学习者查阅;第四章介绍英语、翻译和商务英语专业学生学位论文写作经常涉及的五个方向的相关理论、知识及研究话题,并提供一些论文题目供学生学习。简明扼要地介绍英语学术论文写作所需基本理论和技巧,让学生对英语学术论文写作从选题到提纲的编写到资料的收集及相关资料的有效使用等以及论文写作规范有个全面了解,培养学生初步的科研能力,提高其学术论文写作质量及学术素养。本书内容新颖,浅显易懂,实例丰富,工具性强。本教材可供普通本科院校英语、翻译及商务英语专业高年级学生使用。

《英语学术论文写作》内容试读

Basic Information About

Research Paper Writing

“Research”comes from the Middle French word“rechercher,,”meaning“to seek out.."

Writing a research paper requires us to seek out information about a subject,take a stand onit,and back it up with the opinions,ideas,and views of others.What results is a printedpaper variously known as a term paper for a university course,a published article in ajournal,and a thesis or dissertation as a partial requirement for a university degree,inwhich we present our views and findings on the chosen subject.

1.1Characteristics of a Research Paper

Writing a research paper follows the same process as other kinds of expository writing,from planning through drafting and revising.However,a research paper has its owncharacteristics.First,it calls for the use of external sources.We must collect information ona chosen subject from many different sources and incorporate it into the paper clearly andappropriately.Second,a research paper is a very formal piece of writing,and follows aparticular form.There is little room for creativity or individualism.There is little stylisticdifference between the papers written by us and other people.Besides,the informationquoted in the paper,either directly or indirectly,must be carefully documented.So,aresearch paper expresses the author's understanding of the topic based on experiments,facts,data and analyses.It is objective rather than subjective although the author's personalvalues,insights,and experiences have a great influence on the whole writing process.

1.2Types of Research

There are two types of research:primary research and secondary research.

001

Primary research means working in a laboratory,in the field,or with an archive of rawdata,original documents,and authentic artifacts to make firsthand discoveries.Conductinga survey or series of experiments,viewing a series of television programs,interviewingparticipants in a relatively recent event of some importance,and examining authenticdocuments and original records-all belong in primary research.

Secondary research means looking to see what other people have learned and written.

Knowing how to identify facts,interpretations,and evaluations is the key to goodsecondary research.Facts can be measured,observed,or independently verified in someway and therefore are objective (e.g.William Faulkner was born on September 25,1897);interpretations spell out the implications of facts (e.g.he succeeded because he wasextremely diligent);evaluations are debatable judgments about a set of facts or a situation(e.g.it is good for students to try some part-time jobs while studying at college).Once weare up-to-date on the facts,interpretations,and evaluations in a particular area,we will beable to design a research project that adds to this knowledge.Usually,what we will add isour perspective on the sources we found and read.

1.3 Types of Research Papers

Research papers fall into three categories,with each having a distinctive format.

1.3.1 Papers Based on Empirical Data

Papers based on empirical data,information derived from direct observations orexperiments,often follow a standard format:Introduction,Literature Review,Research

Methodology,Results (Findings),Interpretation and Conclusion.As to what to include ineach chapter and how to write it,some writers-Slade and Perrin,Hubbuch,etc.,have madea clear explanation in their books.Here we will just make a brief review.

1.Introduction

In Introduction we should introduce the general area of investigation (the generalsubject)and the specific hypothesis we tested,inform the reader about the theories onwhich our study is based and about the published research projects that we have drawn onto develop our hypothesis and methodology,and explain to the reader where our study fitsin the general picture of the current theories and the work that has been done.Simply put,we should briefly and clearly state our purpose in writing the paper,provide the mostimportant background information,state the method(s)of investigation and the reasons,and

002

then present the principal results of the investigation and the principal conclusionssuggested by the results

2.Literature Review

Literature review,usually a separate section,should establish for the readers thecontext of our study.It should call attention to the most important previous work,identifythe place of our work in relation to the other research,and delineate areas of agreement anddisagreement in the field,not just make a summary of a series of books and articles;itshould evaluate and interpret the existing research,not just repeat it.Organizing the reviewby topic rather than by author and avoiding unnecessary quotation can help us focus thereview of research.

Without doubt,not every paper based on empirical data has a Literature Reviewsection;in some papers "literature review"is briefly incorporated into Introduction.

3.Methodology

This chapter can also be headed Method(s),Methods and Procedures,Materials and

Methods,or Experimental Section.It is intended to answer the how and what questions in away that enables other researchers to replicate or redo a study or experiment exactly as itwas first done.So the materials or subjects employed as our source for raw data,the stepstaken to acquire our data and the data themselves should be described.If it is complicatedor long,it can be divided with several headings or subheadings,which are devoted to suchinformation as the participants,materials,and procedures.For instance,in the followingsample paper "The Role of Exposure to Isolated Words in Early Vocabulary Development"the second part is headed Method,which includes“Subjects,.”“Procedure,.”and"Transcription and tabulation."

In sum,for papers based on empirical data,the Method section typically consists of thefollowing subsections:

●Design

Is it a questionnaire study or a laboratory experiment?

Subjects or participants

Who took part in the study?What kind of sampling procedure did we use?

●Instruments

What kind of measuring instruments did we use-experiments?questionnaires?interviews?observations?all of them used together?Why did we choose them?Are theyvalid and reliable?

●Procedure

How did we carry out our study?What activities were involved?How long did it take?

003

4.Results(Findings)

This chapter usually begins with a straightforward report of the results or findings andan explanation of the procedures used to obtain those results.The results of theinvestigation,positive as well as negative,should be presented in clear,coherent prosewithout interpretation or evaluation.Tables or figures are often used,but they shouldsupplement the text,not substitute for it.The body of the paper should be comprehensibleon its own,even if readers choose not to consult the tables.

5.Interpretation and Conclusion

After describing the results,we should evaluate and interpret the data and formulateconclusions.We need to tell the reader what we learned,in more general terms,by doingthis study.The implications of the findings for revising the existing body of the knowledge,the relation of the results to previous research,limitations of the study,unexpected findings,practical applications of the findings or speculation about further research-all can becovered here.

In a word,writing research papers based on empirical studies requires us to haverelevant research bases,adequate theoretical knowledge,appropriate experimental subjectsand enough time for doing research and writing.Here is a journal article based on empiricaldata,but because it is too long,only Introduction and Conclusion (Discussion)and thesection headings in the body are retained.

The Role of Exposure to Isolated Words in Early Vocabulary Development

Michael R.Brent,Jeffrey Mark Siskind

1.Introduction

Between the ages of 9 and 21 months,children typically progress from speaking at most ahandful of words to speaking over 200(Fenson,Dale,Reznick,Bates,Thal,1994).To learn a word,a child must store its sound pattern,its meaning,and an association between the two.Since fluentspeech contains no known acoustic analog of the blank spaces between words of printed English,children must segment the speech signal in order to learn words from multi-word utterances.Early inthe study of language acquisition,the segmentation problem received little attention;it was tacitlyassumed that children learned words primarily from isolated occurrences.In the 1980s,it wassuggested (Peters,1983;Pinker,1984)that words learned in isolation could help children segmentmulti-word utterances containing novel words.However,there was little systematic empirical evidencefor this hypothesis.In fact,there was some evidence that infant-directed speech does not reliablyprovide isolated words(Aslin,Woodward,LaMendola,Bever,1996).

In the last 10 years there has been tremendous progress in understanding infants'ability tosegment fluent speech.By 7.5 months,infants can recognize words that they have heard in

004

fluent speech when those words are later presented in isolation (Jusczyk Aslin,1995)and caneven do so after a 2-week delay (Jusczyk Hohne,1997).Further,8-month-old infants are ableto exploit patterns in sequences of nonsense syllables to help isolate word-like units fromsynthesized speech that lacks any other segmentation cue (Saffran,Aslin,Newport,1996).

This research has been accompanied by a shift away from the view that early vocabularies arelearned primarily from isolated words.

In this paper,we revisit the potential role of isolated words in early word learning.It haslong been known that infant-directed speech tends to consist of short utterances (e.g.Snow,1977)separated by relatively long silent pauses (Fernald et al.,1989).Recently,the question ofisolated-word frequency has been addressed in a study of a single subject(van de Weijer,1998).

This paper reports a multi-subject investigation of four empirical questions:

1.Are isolated words a normal and reliable feature of spontaneous infant-directed speech?

2.Do children hear repeated instances of a variety of distinct words in isolation?

3.Does a significant proportion of children's earliest vocabularies consist of words that theyhave heard in isolation?

4.Does exposure to isolated instances of a word predict later knowledge of that word,above and beyond total frequency of exposure?

If the answer to all four questions is "yes",that would suggest that children may benefitfrom the presence of isolated words during the first year of word learning

2.Method

2.1 Subjects

2.2 Procedure

2.3 Transcription and tabulation

3.Results

3.1 Frequency and reliability of isolated words

3.2 Diversity and repetition of isolated words

3.3 Proportion of early vocabulary heard in isolation

3.4 Predictive power of exposure to isolated words for subsequent vocabulary

4.Discussion

The data and analyses described above provide positive answers to the four empiricalquestions posed in Section 1.First,isolated words are a regular occurrence in the experience ofalmost every infant in the population from which this sample was drawn.Second,the isolatedwords to which infants are exposed comprise a variety of distinct word types,a number of whichare repeated in close temporal proximity.Third,a substantial proportion of the first 30-50 wordsproduced are words typically spoken in isolation by mothers to their infants before they are usedby the infants.Finally,the frequency with which a given mother speaks a given word in isolationis a statistically significant predictor of whether her child will be able to use that word at a later

005

date.However,the total frequency with which she speaks a word is not a statistically significantpredictor of her child's later word use.

The finding that about 9%of infant-direct utterances are isolated words is consistent withseveral previous analyses of single subjects (Siskind,1996;van de Weijer,1998).However,thefinding that isolated word use is reliable across mothers is not consistent with an earlier study(Aslin et al.,1996).This difference may result from differences in the experimental methods.

First,the current study analyzed spontaneous speech produced in the home,whereas the earlierstudy analyzed speech produced in the lab in response to a specific task.Second,the currentstudy analyzed a much larger sample per subject.Third,the current study analyzed all isolatedwords produced by the mother,whereas the previous study focused on words related to the task.

A number of previous studies have measured the potential of maternal speech to influencechildren's later knowledge.Studies focusing on syntax have found a very limited influence ofmaternal speech on children's later productions (e.g.Newport,Gleitman,Gleitman,1977).Inthe domain of word learning,Huttenlocher,Haight,Bryk,Seltzer,and Lyons(1991)found that theamount a mother speaks to her child is correlated with the child's rate of vocabulary growth at16-24 months.However,the current study is the first to focus on isolated words.The results areconsistent with the findings of Huttenlocher et al.(1991),and suggest that the greater number ofisolated words resulting from greater total maternal speech may have been the mechanism ofinfluence.Our results are also consistent with recent findings that suggest possible routes ofinfluence but do not measure that influence directly.For example,cross-linguistic studies haveshown that infant-directed speech is slower,higher pitched,and exhibits a wider,more sing-songpitch range (Fernald et al.,1989)and clearer vowels (Kuhl et al.,1997;Ratner,1984)thanadult-directed speech.Further,infants prefer listening to infant-directed over adult-directedspeech(Cooper Aslin,1990;Fernald Kuhl,1987;Werker,Pegg,McLeod,1994).

The findings reported above are based on an English-speaking population.Ultimately,it willbe important to extend these results to other languages and cultures.Nonetheless,there areseveral reasons to be optimistic that the phenomena reported here are characteristic ofcaretaker-child interaction in general.First,a number of other qualitative properties ofchild-directed speech have been found in several languages (e.g.Fernald et al.,1989;Kuhl et al.,1997).Second,our finding regarding the frequency of isolated words in infant-direct speech isconsistent with results reported for a Dutch-German bilingual household (van de Weijer,1998).

Third,although naming objects for children is rarer in some cultures than it is in America (e.g.

Fernald Morikawa,1993;Gopnik Choi,1995),naming does not account for a preponderance ofthe isolated words in our sample;many are utterances such as“come",“go",“now",and“up"

These utterances serve mundane communicative functions that are likely to exist in any culture.

Finally,it appears that even in agglutinative languages like Finnish and Inuktitut,child-directedspeech contains many words in citation form (Inuktitut:S.Allen,pers.commun.;Crago Allen,1998;Finnish:A.Vainikka,pers.commun.).If child-directed speech were like adult-directed speechin these languages,children might hear each inflected form of a word very rarely.

006

···试读结束···

作者:李珍妮

链接:https://www.58edu.cc/article/1713038554340343810.html

文章版权归作者所有,58edu信息发布平台,仅提供信息存储空间服务,接受投稿是出于传递更多信息、供广大网友交流学习之目的。如有侵权。联系站长删除。